“The corporation did to business what the doctrine of Blitzkrieg would do to warfare in 1939: move humans at the speed of technology instead of moving technology at the speed of humans.”

In a recent survey by the non-profit firm Just Capital a growing number of respondents across the political and social spectrum expressed their distrust of corporations.Calling things “corporate” is now a kind of shorthand for all that is cynical, profit driven and faceless — the promotion of a profit-generating entity at the expense of the individual. But what does “corporate” mean in 2016?

Corporations have been around in some form or another since the Romans, but the modern version’s influence has not only grown, but changed into something altogether new. As they reshape the social landscape corporations have become paradoxically both more insidious and more pervasive. The combination of technology that makes markets easily quantifiable and globalization has turned corporations into a parallel state without borders. [1]

A few corporations now control a huge percentage of the wealth and a small number of them control whole sectors of the economy. Media ownership, for example, has become concentrated even as online sources proliferate. The results can sometimes be contradictory or counter-intuitive. It’s a golden age for television but a dark time for journalism. There has been an explosion of small companies thriving in the specialty food market, while food giants like Nabisco and PepsiCo expand horizontally and vertically. Corporations can now contribute to political campaigns as if they were people, while people have access to broadcast channels once only available to huge companies. Superficially, consumers have more choice than at any time in history, but in many ways they have less independence than ever.

Ironically, a major critique of the Communist economic model was that lack of competition led to limited choices for the consumer. My 9thGrade history teacher explained it in the simplest terms by asking us to imagine a state that decided how many pencils were produced every year and in what color. “So if they decided all 10,000 pencils would be red this year and you wanted one in blue, tough luck!” he told us as we listened, horrified. Choice — endless mind-numbing choice — is the selling point for a capitalist system that is ostensibly the envy of the world. While travelers go to Europe for the monuments and museums, Asia for the temples and Africa for the natural beauty, they come in large part to American cities like New York to shop.[2]

Ironic then that consumer choice is one thing that has suffered in this age of mega-capitalism. Those espousing free markets and deregulation have created a kind of corporate state monopoly. In my neighborhood I have only one choice of Internet provider (not surprisingly the service is terrible). In many small American towns consumers have as much choice as travelers in an airport terminal – the same group of national chains is replicated like a wallpaper motif across the continental landscape.

[1]This is comparable to the “Red Sox Nation” phenomenon wherein the fans of a city’s sports team are a geographically amorphous mass, a trend that has been replicated on a global scale with European soccer teams like Barcelona FC or Manchester United

[2]It’s telling as others have commented that in the days after 9/11 president Bush famously told Americans to shop, an expression of fealty to consumerism that was understood as shorthand by Americans for returning to our normal lives by doing the things which best defined us.

We are witnessing the mallificaton of American life. From channel grids to the packaging of professional sports, an assembly line process has maximized efficiency (and profit) while obscuring the human fingerprint that once existed on things.In Manhattan, quirky, family-run coffee shops and restaurants are being edged into oblivion by familiar logos. The other day I walked by one of those Greek family-owned diners in Midtown and its soft interior lights shone like a beacon from another era. The bright yellow plastic sign had some optimistic crudely-rendered space-age iconography from a time when landing on the moon seemed like a fanciful idea. It’s a dying breed.

The corporate instinct professionalizes capitalism and trims away its rough edges so that every sector — from newspapers to soft drinks to films— adheres to the same set of unwritten rules. Once upon a time there were countless American car manufacturers until consolidation took hold and GM, Ford and Chrysler swallowed up the minnows of their industry. Grocery store shelves were filled with 7-Up and RC Cola and the like until Coca-Cola and its surrogate beverages crushed competitors. You Tube (and the internet generally) was once an anarchic amateur Gong Show that sprouted organically like an untended field. (One relic from that era that still exists is the brilliantly pointless site superbad.com.) In the search-optimization era it has become a good corporate citizen. Notice how standardized the design of commercial sites has become, right down to the same click-bait ads running along the bottom or right column?) Like the junkies and porn theaters of Times Square, the weirdness of the web seems to have been banished to the outskirts.

More insidiously, corporatization has taken hold in previously not-for-profit enclaves like prisons, colleges and the health care industry, where a cynical bottom-lineism has taken hold. The recent case of a drug company CEO who raised the price of a life-saving medication from $13.50 to $750 per pill can be argued away as an aberration but it’s also the logical and inevitable result of an instinct taken to its extreme.

Advertising and Marketing

Advertising and marketing are the twin engines that power corporations and the field has evolved almost beyond recognition since the Mad Men era. Marketing, a relatively recent phenomenon, was once only a small part of a corporate sales strategy but has now infiltrated every aspect of social interaction.

Sales used to mean a guy in a cheap suit going door- to-door hustling encyclopedias and vacuum cleaners[3]. Now, marketing is a cloaking device used to sponsor good causes like breast cancer research and “green” initiatives even if the good it does pales in comparison to the self-promotion achieved. It’s the pseudo-hipster presence that sponsors rock festivals and “art events” like a neighborhood rich-kid who tries to make friends by paying for everything.

Cool hunting is an industry, now. And when it comes to social media, the work is being done for the big brands. What they once sought through surveys, polls and laborious market research is being delivered into their laps in real time. Advertisers would have once killed to know what people talked about in the privacy of their homes and how and when and with whom they consumed their products.

What we call nostalgia is in some ways a longing for capitalism in its infancy. Design was iconoclastic and technology only worked intermittently. Advertising was the product of individuals instead of focus groups and in retrospect looks charmingly naïve. As capitalism is perfected by slick, sophisticated corporate machinery, their workings become invisible.

Marketing as social proxy

Advertising also has an important role as a kind of proxy social justice tool. The stubborn social problems which defy solutions are “solved” in ads that present positive images of the marginalized — old people, the overweight, the disabled — and a vision of racial harmony. This has the effect of making people feel better about themselves, society, and of course, the brand. The United Colors of Benetton campaign promoted the idea that all of us could get along (provided we were all young and attractive presumably). One of the earliest examples of this approach (which is either brilliant or deeply cynical depending on your point of view) was in 1971 when Coca-Cola taught the world to sing in “perfect harmony” (thus achieving a kind of perfect harmony between commercial and altruistic instincts, and more recently providing Mad Men with a perfect ending) In the process it taught the rest of the advertising world that products weren’t sold on the character of their content as much as the content of their (corporate) character.

[3]I remember a man showing up at our door hawking vacuum cleaners doing the whole demo complete with mound of dirt spilled on the carpet and small metal balls sucked into the vacuum cleaner’s guts to demonstrate its power.

This fiction of social harmony of course extends to the portrayals in mainstream films and TV shows. Black guys and white guys (who in real life still live in separate Americas) team up to solve crimes, get into capers and are best friends and neighbors. That’s why so many (usually white Middle and upper class) Americans are so shocked whenever this veil is lifted and we get a glimpse of a country that has been there all along.Hurricane Katrina revealed that many poor black people live in third-world conditions in a smaller America inside the larger one. The events of Ferguson, Missouri exposed communities that are angry, beat-down, disenfranchised, separate and unequal – nothing like the Cosby fiction that represents supposedly post-racial America. The popular narrative espoused by Sony, McDonald’s, NBC and the rest of the corporate-entertainment complex is that segregation and racism are mostly a thing of the past to be made light of in buddy-cop movies, mythologized in period documentaries or alluded to in sepia-toned tributes during the Olympics or NBA Finals.

Advertising colonizes cultural ideas the way empires once colonized nations, strip-mining their most valuable elements and disregarding the rest. Coke and Volkswagen used images of hippies in the ‘60s to sell cars because they had “groovy threads” that appealed to their target demo but ditched their accompanying political views. In the ‘70s advertising icons looked like cocaine-sniffing swingers but projected family values that made them the ideal spokespeople for deodorant, cars, and life insurance. The same goes for Gay men in ‘80s ads who had cultural currency as arbiters of good taste but were otherwise expected to stay in the closet. Advertising wants the sizzle but has no appetite for the steak.

Advertising is Salvador Dali hamming it up to sell chocolate and Alka-Seltzer, the very urbane George Plimpton hawking video games or (perhaps most depressingly) Lou Reed cashing in on his song about downtown misfits and trannies to advertise scooters. Public personalities who had become famous for doing their thing in the “real world” are then paid to recreate their personas in this artificial setting. They are like wild animals that have been tamed within the nature reserve that is the marketplace. Context of course is everything. (Honda knew enough to use an instrumental version of Reed’s song to excise the more explicit lines in Take a Walk on the Wild Side.) The iconography of any given era — avant-garde artists, hipster beards, sleeve tattoos — are used as seasoning the same way a luxury apartment dweller likes just a hint of urban grit in his or her neighborhood, but no more. Authenticity is an accent not a lifestyle.

Ads are there to tell us it’s ok to want things. And that’s it’s normal to want things. That it's normal to feel unfulfilled and want to fill that void with family and love, but all they have to sell are things so they connect the two. They can protect you from scary things and provide comfortable (or comforting) things when you feel bad and efficient things when you’re overwhelmed.

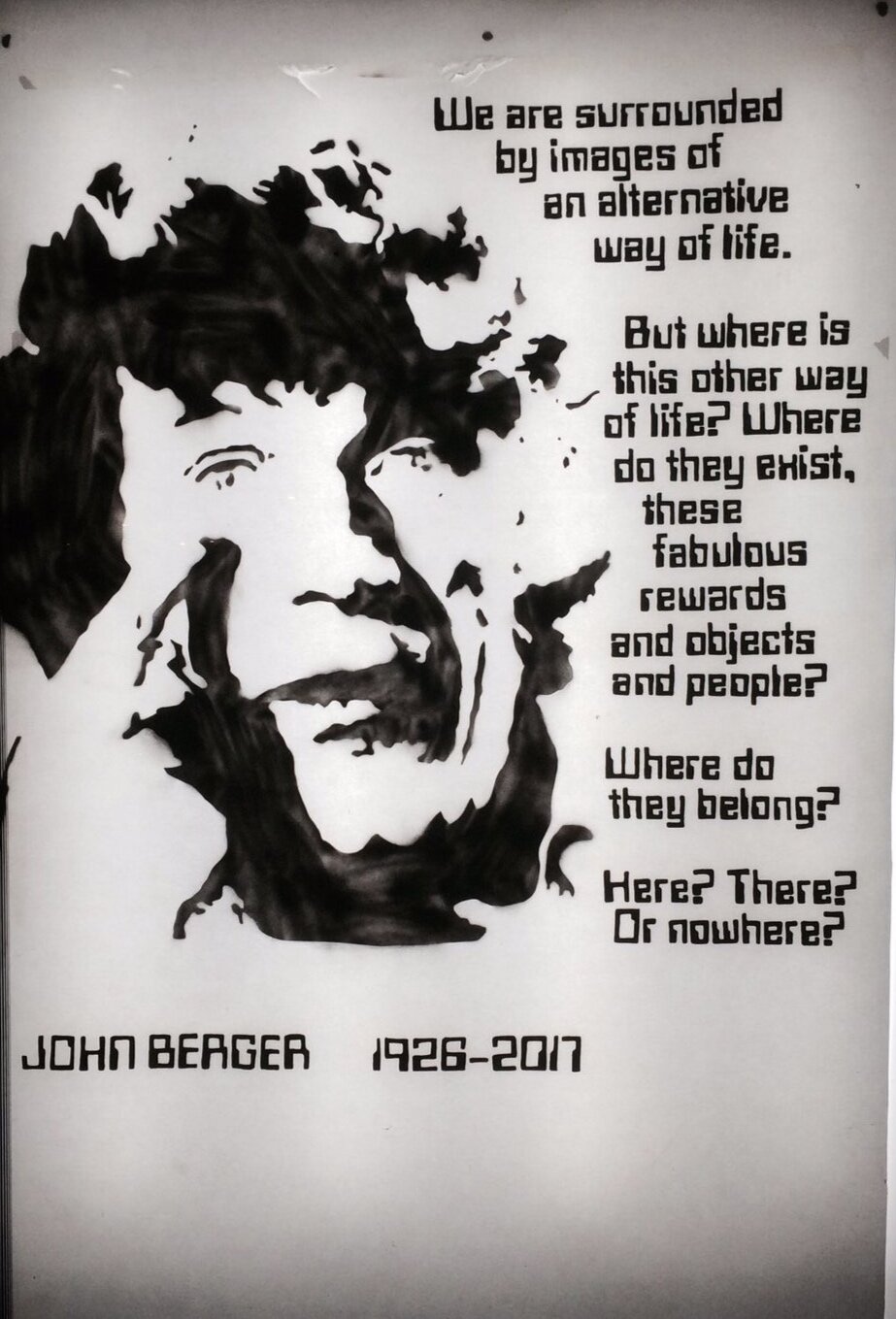

Here is John Berger on the subject in his seminal 1972 text “Ways of Seeing”:

“It (publicity) proposes to each of us that we transform ourselves, or our lives, by buying something more.

This more it proposes will make us in some ways richer — even though we will be poorer by having spent our money.

Publicity persuades us of such a transformation by showing us people who have apparently been transformed and are, as a result, enviable. The state of being envied is what constitutes glamour. And publicity is the process of manufacturing glamour.”

Love, family, loyalty, fear, etc could not be sold directly – only its symbols. Until now. Facebook is possibly the most perfect and perfected example of a corporate entity ever made. It converts social interaction into currency with Orwellian efficiency. Ads now have the ability to follow you around the web like a persistent salesperson who won’t take no for an answer. Once you could shut the door or hang up the phone, but now the connection between sales pitch and consumer cannot be easily severed. Our history of interests is embedded into our online profiles.

Brands

Previously only products were known as brands, now individuals, sports teams, and even countries have a marketability factor. People are encouraged to market themselves to the wider world the way only companies once did. Brand loyalty has in many ways replaced previous forms of worship.

A few years ago I was riding the subway in New York and saw something amazing. A woman in her 20s had tattooed two large matching NY Yankee logos on each of her calves, branding herself like so much livestock.

When scandals have hit stars like Bill Cosby or Tiger Woods, the severity of their predicament isn’t gauged by how far they have fallen afoul of the legal system as much as how deeply they have alienated their corporate sponsors. One can cop a plea with the justice department but Nike and Jell-O Pudding cannot be placated so easily.

The singularity, corporation style

There is a theory gaining popularity lately known as the singularity. The general idea is that as artificial intelligence gets more sophisticated, people and machines will gradually merge into one. While I was initially dubious I’m starting to believe in a corporate version of this future. People seem to be on a seemingly voluntary collision course with their devices. Evidence to support both versions of this theory can be seen in the creepy ad campaigns currently popular in which regular people interact with their smart phones as if they are their friends, a goal explicitly encouraged by Apple who say on their website “Talk to Siri as you would to a friend”.

A succession of ads showing people talking to machines as if they were people (including a very painful one with Bob Dylan) is certainly disturbing evidence of this, as is the new app called Peeple that rates people as if they were products,.

The individual — multifaceted, complex, contradictory — is reduced to a 2D image and signifier of a product’s and by extension a person’s value (Jennifer Lawrence posing with a luxury watch or Serena Williams endorsing a bank) society’s elites paired together in mutually reinforcing associations.

Individual as entity, corporation as friend

Yet, while a lot of people have ambivalent feelings about large corporations the incentives they offer mean that many consider it a great privilege to work for them. For years my mother encouraged me to apply work for “a big company” presumably because they would take care of me like some sort of surrogate family unit, which is how they sell themselves to employees. Or as friends.

Corporations, while presenting themselves as our friends, are ruthless in their protection of their brands. In 1994 McDonalds actually sued a 9-year-old girl because the name of a game she invented conflicted with their marketing campaign.

The corporate entity as “friend” is another recent development and is reflected in the copy we see now on product labels, which has a kind of contrived “aw shucks” humility. As the personification of the American corporation evolves its corollary of course is the corporatization of the individual. Here is Eric Schlosser in Fast Food Nation:

“A corporate memo introducing the campaign explained: "The essence McDonald's is embracing is 'Trusted Friend' ... 'Trusted Friend' captures all the goodwill and the unique emotional connection customers have with the McDonald's experience ... [Our goal is to make] customers believe McDonald's is their 'Trusted Friend. Note: this should be done without using the words 'Trusted Friend' ... Every commercial [should be] honest ... Every message will be in good taste and feel like it comes from a trusted friend.”

The corporate world is one of proxies and representatives, spokespeople and PR professionals who are paid to swaddle the truth in so many layers it becomes virtually indistinguishable. This is one explanation for the appeal of any public figure who projects a visceral, unfiltered persona that now seems a relic of another age, no matter how idiotic (Donald Trump) vulgar (Howard Stern) or asinine (Anne Coulter).

Sports, for instance

The evolution of sports are an example of the stark effects of corporatization, in an industry once run by cigar-chomping patriarchs and now under the control of lawyerly corporate behemoths. Players used to play for their cities, pride and a modest paycheck. Now they increasingly represent their unions, the league itself and their corporate sponsors. Another telling example from the world of major professional sports in North America (thankfully a phenomenon that has yet to spread across the globe) is the ritual that occurs when teams are crowned champions. As soon as time expires and before the trophy presentation, some corporate minion hurriedly outfits every member of the winning team in a championship hat with league branding, as if to reinforce the fact that the league on some level supersedes each individual player and each team. What if one player one day simply refused to wear one of these hats at this crucial moment, reclaiming the individual over the corporate? As far as I know it hasn’t happened yet.

The experience of going to a professional sporting event (or any public event really) was much more sensory and organic in my lifetime. Old arenas and stadiums smelled like cigarette smoke and cheap after-shave and spectators were closer to the players in both a literal and figurative sense, watching the action on small seats or in standing-room only sections huddled together. The game itself remains as un-predictable and as thrilling as ever, but all that surrounds it now belongs among the narrower registers of the human experience.

For Millennials, who were born into this corporatized environment all of this seems to be embraced as a matter of course. One night recently I was out with a group of work colleagues and we were marveling at a tower of beer that came in the form of a glowing LED structure that spewed dry ice. A couple of the women (in their early 20s) filmed the spectacle on their phones and then posted the results immediately on Instagram. One sitting across from me showed me the clip and said, “you have to like it,” meaning of course on social media. “I do like it,” I responded disingenuously, knowing of course what she meant. “No you have to click a button,” she said, with self-awareness but also a hint of neediness in her voice.